How I Slashed Senior Education Costs Without Sacrificing Quality

Paying for senior education later in life can feel overwhelming. I was once stressed about balancing learning dreams with a fixed income. But after testing real cost-control methods, I saved significantly without cutting corners. In this guide, I’ll walk you through practical strategies that actually work—backed by experience, not theory. These aren’t get-rich-quick tricks, but smart, sustainable ways to protect your finances while investing in knowledge. Whether you're exploring art history, mastering digital tools, or learning a new language, the financial burden doesn’t have to overshadow the joy of growth. With thoughtful planning and informed choices, it’s entirely possible to pursue lifelong learning without draining your retirement savings. This is not about sacrifice—it’s about strategy.

Why Senior Education Often Drains Retirement Budgets

Many retirees enter continuing education programs with high hopes but incomplete financial awareness. The excitement of learning something new can overshadow the reality of cost accumulation. Tuition fees are just the beginning. Registration charges, textbook purchases, technology requirements, and even transportation to campus or event-based workshops all contribute to the total expense. These additional costs often go unnoticed until the bill arrives, leaving many seniors surprised by how quickly a single course can impact their monthly budget. A program advertised at $300 might end up costing $600 or more once all associated fees are included, especially if certification or specialized materials are involved.

The financial strain is magnified when multiple courses are taken in succession. Without a clear spending limit, continuous enrollment can resemble a recurring subscription—one that competes directly with essential retirement expenses like healthcare, home maintenance, or family support. I learned this the hard way when I enrolled in a six-week personal finance seminar without reviewing the full cost structure. The advertised price was $199, but after purchasing the required financial planning software and a printed workbook, my final outlay exceeded $450. That experience taught me that emotional motivation—while powerful—can distort financial judgment. The desire to grow, stay mentally active, or fulfill a lifelong dream is valid, but it must be balanced with fiscal responsibility.

Another overlooked factor is the opportunity cost of time. Retirees often underestimate how much time a course demands and how that time could otherwise be used for volunteer work, part-time income generation, or family engagement. When time and money are both limited, every educational choice should be weighed carefully. Programs that promise broad benefits but deliver minimal practical value can leave learners feeling not only financially strained but also emotionally disappointed. This is particularly true for short-term workshops that emphasize inspiration over skill-building. While motivational content has its place, it should not come at the same price as a technical or vocational course with measurable outcomes.

Understanding these hidden drains is the first step toward financial control. Recognizing that education costs extend beyond tuition allows retirees to plan more accurately and avoid unpleasant surprises. It also encourages a shift from reactive enrollment—signing up based on emotion or urgency—to intentional learning, where choices are made with both personal interest and financial sustainability in mind. By mapping out potential expenses in advance and asking detailed questions before enrolling, seniors can protect their retirement funds while still pursuing meaningful intellectual growth.

The Mindset Shift: Treating Learning Like an Investment, Not an Expense

One of the most transformative changes I made was reframing how I viewed education. Instead of seeing each course as a necessary expense, I began treating it as a strategic investment in myself. This subtle but powerful shift changed not only how I spent money but also how I selected programs. Just as a homeowner evaluates the long-term value of a renovation before spending thousands, retirees should assess whether a course will deliver lasting benefits. Will it improve daily life? Enhance confidence? Open doors to new social or volunteer opportunities? These are the kinds of returns that justify spending, even on a fixed income.

Consider two hypothetical courses: one is a $1,200 photography class offered by a well-known arts institute, complete with branded materials and a certificate. The other is a $150 community-led workshop that focuses on practical skills like lighting, composition, and digital editing using free software. On the surface, the first option appears more prestigious. But if the second delivers the same core skills and allows you to take better family photos, document travels, or even contribute to a local newsletter, its real-world value may far exceed the pricier alternative. The key is not the price tag, but the utility and usability of what you learn.

I once enrolled in a highly promoted digital storytelling course because it was hosted by a popular instructor. The marketing promised “life-changing creativity” and included a sleek course website and video introductions. But after completing the program, I realized I had learned very little that I could apply. The lessons were vague, the assignments repetitive, and the feedback minimal. In contrast, a later course on genealogy research—costing only $75 through a local historical society—gave me clear methods for organizing family records, using public archives, and creating a simple family tree. That knowledge led to hours of meaningful connection with my grandchildren and a preserved family legacy. The lower-cost course delivered a far greater personal return.

Treating education as an investment also means being willing to delay gratification. Just because a course is available now doesn’t mean it’s the right time to take it. Waiting for a discounted enrollment period, a scholarship opportunity, or a free public offering can significantly reduce cost without diminishing value. It also allows time to research alternatives, read reviews, and consult with others who have taken the program. This disciplined approach turns impulsive spending into intentional planning. When every dollar spent on learning is evaluated for its long-term impact, education becomes not a financial burden, but a purposeful enhancement to retirement life.

How to Spot High-Value, Low-Cost Learning Opportunities

Quality education does not require a luxury price tag. Across the country, public institutions and nonprofit organizations offer affordable or even free learning options tailored to older adults. Community colleges, for example, frequently provide non-credit enrichment courses in subjects ranging from literature and philosophy to computer basics and financial literacy. These programs are often priced at a fraction of university tuition and sometimes offer senior discounts or waived fees for those over a certain age. I discovered that my local community college allowed residents aged 60 and above to audit most non-credit classes for just $25 per semester. That small fee gave me access to lectures, classroom discussions, and instructor guidance without the pressure of grades or assignments.

Public libraries are another underutilized resource. Many have partnerships with online learning platforms like The Great Courses, Gale Courses, or LinkedIn Learning, providing cardholders with free access to thousands of video-based lessons. These platforms cover everything from travel photography to mindfulness practices and are accessible from home with a library login. I used my library’s subscription to complete a full course on home vegetable gardening, which later helped me start a small backyard plot that reduced my grocery bills. No additional software, tools, or memberships were required—just a library card and an internet connection.

Universities with continuing education divisions also offer valuable opportunities. Some allow seniors to audit undergraduate courses for a minimal fee, especially during less busy semesters. Others host public lecture series or lifelong learning institutes specifically designed for retirees. These programs often emphasize discussion and intellectual engagement over testing, making them ideal for those seeking enrichment without academic pressure. I attended a university-hosted lecture series on American history that cost only $40 for eight weekly sessions. The professor was engaging, the materials were provided online, and the small group setting encouraged thoughtful conversation.

Timing and awareness are critical. Many institutions offer early registration discounts or last-minute openings at reduced rates. Signing up for email newsletters or following local education providers on social media can alert you to these opportunities. Additionally, some organizations offer sliding-scale fees based on income, which can further reduce costs for those on a fixed budget. By being proactive and informed, seniors can access high-quality learning experiences that align with both their interests and their financial limits. The key is not to assume that low cost means low quality—but to investigate, compare, and choose wisely.

Leveraging Technology to Cut Learning Expenses

The digital revolution has democratized access to knowledge, making self-directed learning more affordable than ever. With a reliable internet connection and a basic device, retirees can access world-class instruction from universities, experts, and institutions without leaving home. Platforms like Coursera, edX, and Khan Academy offer free or low-cost courses in subjects ranging from psychology to programming. While some charge for certificates, the core educational content is often available at no cost. I completed a full course on personal nutrition through edX, taught by a professor from a leading public university, without spending a dollar. The lectures were clear, the materials were downloadable, and I could watch them at my own pace—pausing, rewinding, or rewatching as needed.

Open Educational Resources (OER) are another powerful tool. These are freely accessible, openly licensed materials used for teaching, learning, and research. Many textbooks, study guides, and lesson plans are available online at no cost, eliminating the need to purchase expensive course materials. I used OER textbooks to supplement a local history course, avoiding a $90 book purchase. These resources are often peer-reviewed and updated regularly, ensuring accuracy and relevance. By combining free digital materials with in-person or community-based learning, seniors can create a hybrid education model that maximizes value and minimizes cost.

Peer-led study groups and online forums also enhance learning without adding expense. Platforms like Meetup or Facebook host groups for retirees interested in book discussions, language practice, or technology help. I joined a virtual Spanish conversation group that met weekly via video call. The group was self-organized, free to join, and included members from different states and countries. The informal setting reduced pressure, and the regular practice significantly improved my speaking confidence. These communities foster accountability and motivation, making it easier to stay committed without paying for a formal program.

However, technology also presents financial traps. Some apps and platforms use freemium models—offering basic access for free but locking essential features behind costly subscriptions. Auto-renewing memberships can lead to unexpected charges if not monitored. I once signed up for a language app with a free trial, only to find a $120 annual fee on my credit card statement months later. To avoid this, I now use a dedicated email for subscriptions and set calendar reminders to review renewals. I also prioritize tools with transparent pricing and clear cancellation policies. By using technology mindfully, seniors can access vast educational resources without falling into hidden cost cycles.

Budgeting Strategies That Keep Education Affordable Long-Term

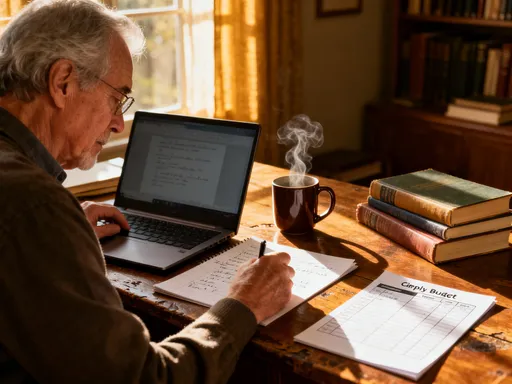

Even when individual courses are low-cost, unmanaged spending can add up over time. Without a clear financial plan, education expenses can become a slow drain on retirement savings. I learned this after reviewing my bank statements and realizing I had spent over $800 in a year on various workshops, apps, and materials—none of which had been budgeted. To regain control, I implemented a simple but effective system: I treated my education spending like a monthly utility bill. I set a fixed amount—$50 per month—that I could allocate to learning without disrupting other financial goals. This created predictability and prevented impulse enrollments.

The concept of a sinking fund was particularly helpful. Instead of paying for a course all at once, I began saving a small amount each month toward future learning goals. For example, if I wanted to take a $300 course in the fall, I started setting aside $50 per month in the spring. This approach removed the financial stress of a large lump-sum payment and allowed me to plan ahead. It also gave me time to evaluate whether the course was still a priority by the time the funds were ready. Often, this waiting period revealed better alternatives or reduced the urgency of enrollment, leading to smarter decisions.

I also began tracking every education-related expense in a simple spreadsheet. This included not just course fees, but also books, supplies, software, and even internet costs if they were used primarily for learning. Seeing the full picture helped me identify patterns—such as overspending on digital tools or underutilizing certain subscriptions. I canceled two app memberships I rarely used and reallocated that money toward a high-value in-person workshop. This level of awareness turned passive spending into active financial management.

Another key strategy was aligning course timing with income cycles. For retirees who receive pension or Social Security payments on a monthly basis, scheduling enrollments right after payment receipt ensures funds are available without dipping into emergency savings. I now plan my learning calendar around my income schedule, choosing to sign up for new courses in the first week of each month. This synchronization creates financial harmony and reduces anxiety about cash flow. By integrating education into my overall budget, I’ve made lifelong learning a sustainable habit rather than a financial risk.

Avoiding Hidden Fees and Financial Traps in Adult Learning Programs

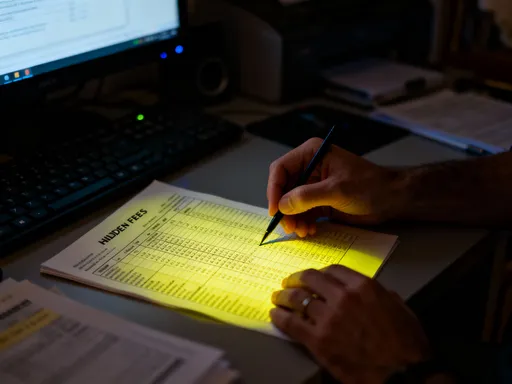

Some education programs attract seniors with low upfront costs but conceal additional charges that significantly increase the total price. These hidden fees can include mandatory materials, certification costs, software licenses, or even “exclusive” access passes. I encountered this when I enrolled in a home organization course advertised at $49. After registration, I was informed that a $250 “starter kit” of bins, labels, and planning tools was “strongly recommended” to complete the program. When I asked if I could use my own supplies, I was told the course activities were designed specifically for the branded materials. This pressure tactic is common and preys on the desire to fully participate and succeed.

To protect yourself, always read the fine print before enrolling. Ask for a complete breakdown of all potential costs, including optional add-ons. Reputable programs will provide this information upfront and allow you to make an informed decision. If a provider hesitates or refuses to disclose full pricing, that should be a red flag. I now make it a habit to email program coordinators with a simple question: “What additional costs should I expect beyond the listed fee?” Their response—or lack thereof—often tells me more than any marketing brochure.

Another warning sign is language that creates urgency or exclusivity. Phrases like “limited-time offer,” “only a few spots left,” or “certification included only for early registrants” are designed to rush decision-making and bypass careful financial review. Legitimate educational institutions do not rely on high-pressure sales tactics. They understand that retirees need time to consider options, consult family, or check their budgets. If a program feels more like a sales pitch than an academic offering, it’s wise to step back and reassess.

Certification fees are another common trap. Some courses advertise themselves as career-advancing but charge hundreds of dollars to issue a formal certificate—even if the document has no recognized value in the job market. Before paying for certification, research whether the credential is accredited or widely accepted in the field. For personal enrichment, a certificate is often unnecessary. The real benefit comes from the knowledge and skills gained, not a piece of paper. By focusing on substance over symbolism, seniors can avoid unnecessary expenses and maintain control over their education spending.

Building a Sustainable Learning Plan That Respects Your Financial Limits

The ultimate goal is not just to save money, but to create a lifelong learning lifestyle that is both enriching and financially sustainable. This requires more than cost-cutting—it demands intentionality, planning, and regular evaluation. I now approach education with a seasonal rhythm, aligning my learning goals with my budget cycles and personal energy levels. In the spring, I focus on outdoor-related courses like gardening or nature photography. In the winter, I turn to indoor topics like cooking, writing, or history. This seasonal approach keeps learning relevant and enjoyable while spreading costs evenly throughout the year.

I also conduct a quarterly review of my learning activities. I ask myself: What did I gain from each course? Was the time and money well spent? Would I recommend it to a friend? This reflection helps me identify high-value programs and avoid repeating low-return experiences. It also reinforces the mindset of education as an investment. When I can clearly see the benefits—whether improved skills, stronger relationships, or greater confidence—I feel more justified in continuing to spend wisely on learning.

Finally, I’ve learned to balance free and paid resources. While free options are abundant, some paid courses offer superior structure, instructor access, or peer interaction that enhance the experience. The key is to pay only when the added value is clear and necessary. I now use a simple rule: if a free alternative exists and meets my needs, I choose it. If a paid option offers something truly unique—like personalized feedback or a hands-on workshop—I consider it a worthwhile investment. This balanced approach ensures I never feel deprived, yet always remain in control of my finances.

Lifelong learning is one of the greatest gifts we can give ourselves in retirement. It keeps the mind sharp, the spirit curious, and the days meaningful. But to be truly fulfilling, it must be pursued with financial wisdom. By treating education as an investment, seeking high-value opportunities, using technology wisely, budgeting intentionally, and avoiding hidden costs, seniors can enjoy the benefits of learning without the burden of debt. This is not about doing more with less—it’s about doing what matters most, in a way that lasts.